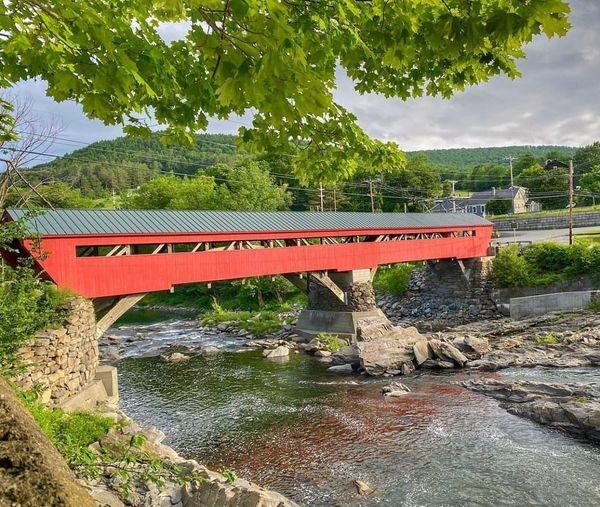

Covered Bridges

Day trip tour from Vermont Cottage. DIRECTIONS~Right turn out of the driveway, and turn right onto Route 100. Head north on Route 100. Take a right on Route 100A. At end of Route 100A take a right onto Route 4. After the Town of Bridgewater, you will see the 1st covered bridge on your right.

·4 min read